Some coral species can be resilient to marine heat waves by “remembering” how they lived through previous ones, research by Oregon State University scientists suggests.

The study, funded by the National Science Foundation, also contains evidence that the ecological memory response is likely linked to the microbial communities that dwell among the corals.

The findings, published today in Global Change Biology, are important because coral reefs, crucial to the functioning of planet Earth, are in decline from a range of human pressures including climate change, said the study’s lead author, Alex Vompe.

“It is vital to understand how quickly reefs can adapt to ever more frequent, repeated disturbances such as marine heat waves,” said Vompe, a doctoral student who works in the lab of microbiology professor Rebecca Vega Thurber. “The microbiomes living within their coral hosts might be a key component of rapid adaptation.”

Heat waves are likely to increase in frequency and severity because of climate change, he added. Slowing down the rate of coral cover and species loss is a major conservation goal, and predicting and engineering heat tolerance are two important tools.

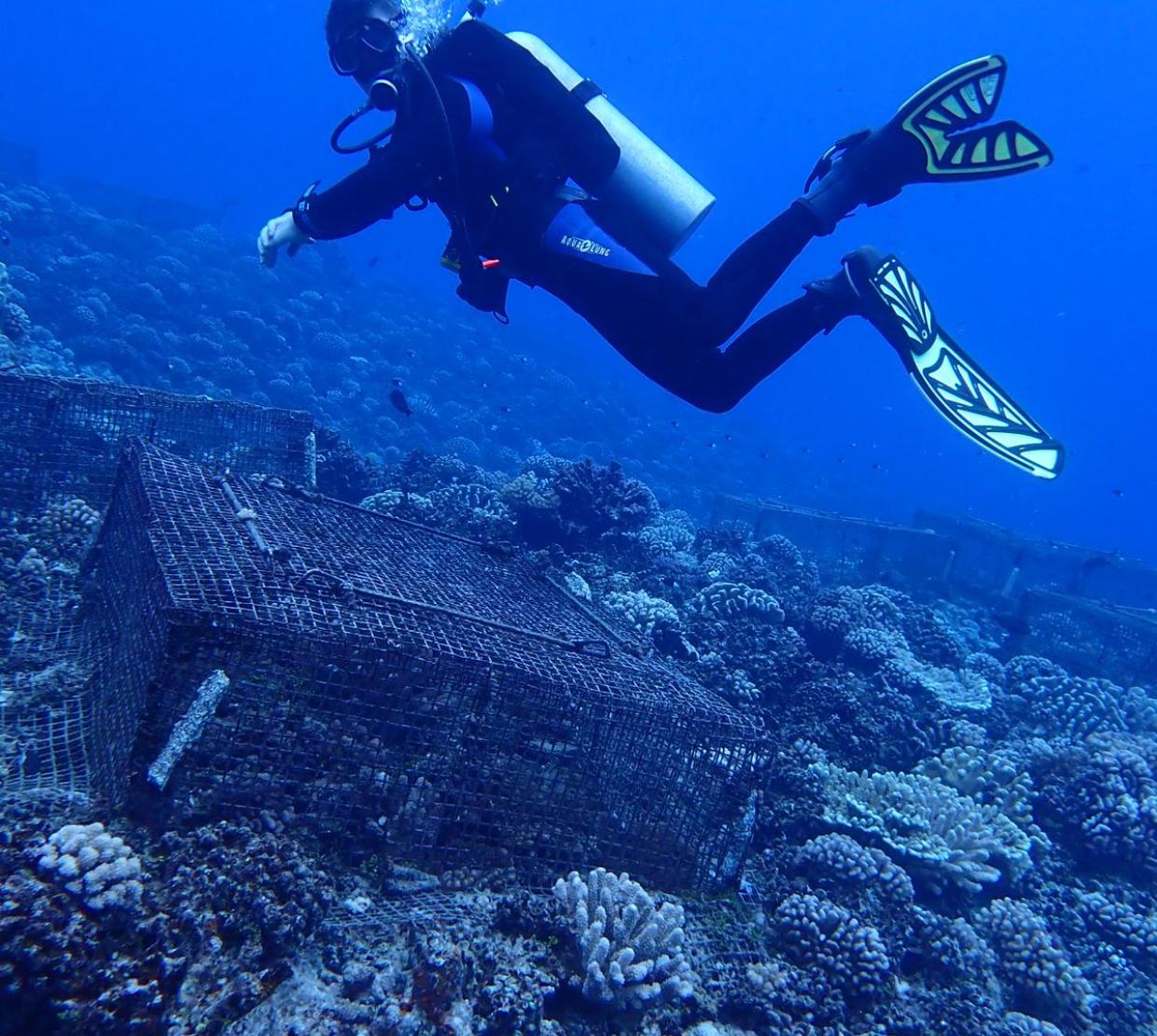

Knowing the role microbes play in adaptation can inform coral gardening and planting efforts, Vompe said. A deeper understanding of the microbial processes, and the organisms responsible for ecological memory, can also aid in developing probiotics and/or monitoring protocols to assess and act on the quality of ecological memory of individual coral colonies.

Coral reefs are found in less than 1% of the ocean but are home to nearly one-quarter of all known marine species. They also help regulate the sea’s carbon dioxide levels and are a crucial source for scientists searching for new medicines.

Corals are made up of interconnected animal hosts called polyps that house microscopic algae inside their cells. Corals also house functionally and taxonomically diverse bacteria, viruses, archaea and microeukaryotes. The community of bacteria and archaea living within corals are referred to as the coral microbiome.

Symbiosis is the foundation of the coral reef ecosystem as these microbes benefit coral hosts by assisting in carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycling, essential vitamin supplementation, and protection against pathogens. The coral polyps in turn provide nutrition and protection to the algae and bacteria.

Climate change is threatening coral reefs in part because some of the relationships between coral and their microbes can be stressed by warming oceans to the point of dissolution – a collapse of the host-microbe partnerships, which results in a phenomenon known as coral bleaching.

Read the full article here.